Schwache Schüler schaden Sozialprodukt

Der OECD kann man nicht unbedingt vorwerfen, dass sie mit ihren vergleichenden Analysen besondere Rücksicht auf die kurzfristige und kurzssichtige Politik nimmt. Political Correctnes ist eher als Weichspüler im Hype der Medienwelt geeignet – OECD-Analysen kommen oft zu anderen Ergebnissen. Weichzeichner haben in der Fotografie-Technik ihren Platz, Schönfärberei hat in der Bildungs- und Gesellschaftspolitik nichts zu suchen.

In den Medien hat derzeit das Mantra der „Flüchtlingsintegration in den Arbeitsmarkt“ Hochkonjunktur, entspricht es doch der Political Correctness des Fata-Morgana-Ansatzes „Wir schaffen das“. Das staatliche Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (IAB) aus Nürnberg oder die OECD lassen kaum eine Gelegenheit aus, auf den Zusammenhang zwischen qualifizierter Schulbildung oder Studiem und den Erfolg am Arbeitsmarkt in der Form von höheren Einkommen und niedrigerer Arbeitslosigkeit hinzuweisen. In krassem Gegensatz dazu stehen die öffentlichen Anmerkungen von Frank-Jürgen Weise, Multi-Tasker bei der Bundesagentur für Arbeit und dem Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, der die Mähr von der erfolgreichen Integration der Flüchtlinge in den Arbeitsmarkt und die Gesellschaft unermüdlich verbreitet. Vermutlich wird er von seiner Chefin zu solchen Aussagen gezwungen „überzeugt“.

Nun legt die OECD eine vergleichende Studie vor und kommt zu einem ernüchternden Ergebnis: Schwache Schüler schaden dem Sozialprodukt, also der Wirtschaft und der Gesellschaft. Deshalb ist eine zielgerichtete Hilfe für diese Bildungsgruppe von ausserordentlicher Bedeutung.

Die Pressemeldung der OECD vom 10.2.2016, nur auf Englisch verfügbar, stellt die Realität ungeschminkt dar.

Helping the weakest students essential for society and the economy, says OECD

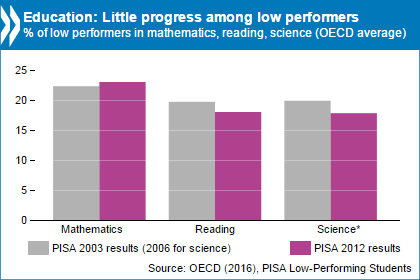

Most countries have made little progress helping their weakest students improve their performance in reading, mathematics and science over the past decade. This means too many young people are still leaving school without the basic skills needed in today’s society and workplace, hurting their futures and long-term economic growth, according to a new OECD report.

“Low Performing Students: Why they fall behind and how to help them succeed” says that around 4.5 million 15-year-olds in OECD countries, equivalent to more than one in four, fail to achieve the most basic level of proficiency in reading, mathematics and/or science. In other countries, the share is often much larger.

Analysing results from the OECD PISA survey between 2003 and 2012 reveals that few countries have seen improvements among low performers and nearly as many have seen their share of low performers increase.

But countries as economically and culturally diverse as Brazil, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Poland, Portugal, Russian Federation, Tunisia and Turkey reduced their share of low performers in mathematics between 2003 and 2012. This shows that reducing the share of low performers is possible anywhere, given the right policies and the will to implement them, says the OECD.

“The social and economic gains from tackling low performance dwarf any conceivable cost of improvement,” said Andreas Schleicher, OECD Director for Education and Skills. “Education policy and practice can help overcome this issue. It needs to be made a priority and given the necessary resources so that every child can succeed at school.”

Click here to download data in Excel for all countries

Low performers also tend to have less perseverance, motivation and self-confidence in maths, and skip classes or days at school more often than better performers. Students at schools where teachers are more supportive and with higher morale are less likely to be low performers, while students whose teachers have low expectations for them and are absent more often are more likely to be low performers.

In countries where educational resources are distributed more equitably across schools, there is less incidence of low performance in maths, and a larger share of top performers, even when comparing school systems whose educational resources are of similar quality.

Analysis also shows that the degree to which advantaged and disadvantaged students attend the same school is more strongly related to smaller proportions of low performers than to larger proportions of top performers. This suggests that systems that distribute both educational resources and students more equitably across schools would benefit low performers without undermining better-performing students.

To break the cycle of disengagement and low performance, the report outlines a series of recommendations. These include:

- Identify low performers and design a tailored policy strategy;

- Reduce inequalities in access to early education;

- Provide remedial support as early as possible;

- Encourage the involvement of parents and local communities;

- Provide targeted support to disadvantaged schools or families;

- Offer special programmes for immigrant, minority-language and rural students;

Low performers are defined as students who fail to reach level 2 in the PISA survey. This means that they can answer questions that provide clear directions and single information sources and connections. However, they typically cannot make more complex uses of information and reasoning. For example, they struggle to estimate how much petrol is left in a tank from looking at the gauge, or have difficulty understanding instructions on an aspirin bottle. Level 2 is considered the baseline level needed for young people to function effectively in today’s workplace and society.